This story is the second of two about Jordan Lake and the work of the Collaboratory’s multi-year study evaluating nutrient management strategies for Jordan Lake. Read the first of the two stories.

By Mary Claire McCarthy

Since 2008, the nonprofit has held 486 cleanups, taken out nearly 20,000 bags of trash and removed 4,727 tires from Jordan Lake. Since its founding, volunteers have hauled out more than 170 tons of trash from 20 miles of shoreline. A ton is equal to 2,000 pounds.

The previous story covering Jordan Lake shed light on the reservoir’s water quality issues; the second part of this series examines trash pollution at Jordan Lake and the connection to more extreme storm events in North Carolina.

Jordan Lake is a reservoir west of Raleigh and south of Durham in Chatham County, though the Jordan Lake watershed covers a more encompassing land area. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has owned and operated the reservoir since they dammed and flooded the Haw River and New Hope River in 1983. The Jordan Lake watershed resides in the Upper Cape Fear River Basin with the watershed streams and creeks ultimately draining into Jordan Lake. As water flows through cities, towns and farmlands, it picks up trash and carries it into our drinking supply sources, namely Jordan Lake.

Trash is more than just an eyesore. Floating and submerged pollution is dangerous to boaters and kayakers. Fishing lines, bite-sized plastics and other pollution can injure birds and animals. Interestingly enough, the Jordan Lake State Recreation Area is home to the highest concentration of bald eagles on the East Coast. Discarded fishing lines could entangle these eagles, while plastic could ultimately poison them.

Local economies may suffer if lake-goers decide to venture to less trash-riddled locations. Chemical residuals in aerosol spray cans can seep into the lake, further contaminating waters that have already been classified as “Nutrient-Sensitive” by the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission. This classification means that the lake is impaired due to excess nutrient pollution levels that are above EPA water quality standards.

Francis DiGiano, the co-founder of Clean Jordan Lake and Professor Emeritus in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says that “if you were to weigh the material on the shoreline that is from recreation, it is a tiny fraction of all that comes there. About 80% of the poundage of trash, and that doesn’t include the tires that are removed, comes from the greater watershed.”

One would expect recreation to be the source of this problem. Surprisingly, trash left behind from people kayaking, swimming, or boating isn’t the major source of garbage at Jordan Lake. With that being said, recreational trash is still a problem that has become markedly more noticeable during the COVID-19 pandemic. DiGiano explains that the Jordan Lake State Park accounts for less than 30% of the lake’s shoreline, meaning that less than 30% of the shoreline has access to trash cans and bathrooms. N.C Wildlife Resources Commission (WRC) manages most of the rest as Game Lands and does not remove trash from the area. That is up to volunteers and citizen consideration.

Where’s the trash coming from then?

Typically though, land development and high rainfall events are the culprits. Anything in the watershed, so anything found on land, can be flushed away by heavy rainfalls directly to Jordan Lake or through storm drains that feed pollution into streams that eventually enter the lake.

Even refrigerators, water heaters and tires are found along the high watermark of many remote coves, especially on the Haw River Arm of Jordan Lake. The Haw River section of the Jordan Lake watershed is one of the two main areas that feed into Jordan Lake. The entire watershed is divided into the Haw River section, which includes the cities of Greensboro and Burlington, and the New Hope Creek section, which includes portions of Chapel Hill and Durham. The Haw River section comprises a land area of about 1,400 square miles with the New Hope River end accounting for an additional 344 square miles. The New Hope River watershed is much smaller in size but highly urbanized. Taken together, roughly 720,000 people live in these two watersheds. You can look at this Google Earth Engine Time Lapse to see the rapid development that’s occurred in these two areas over the last 30 years.

Development converts forests, wetlands and open fields into housing developments and business centers. Natural landscapes slow down the speed and intensity of stormwater by absorbing it into the soil. Conversely, developed landscapes create giant stretches of impermeable cement buildings and sidewalks; these concrete jungles cannot absorb water and instead act as speedways for water.

Clean Jordan Lake keeps records of how rainfall affects the levels of water and trash at Jordan Lake. For example, in March 2009, less than 2 inches of rain early in the month caused the water level at Jordan Lake to increase by 3 feet.

The nonprofit finds trash hundreds of feet into the woods, well above the shoreline, demonstrating that recreational use cannot explain how the trash arrives. Instead, volunteers find garbage far from the shoreline because it is left behind when the water levels return to pre-storm levels. As you might have guessed, when storms drop vast sheets of water from the sky, the lake’s water levels rise. The intensity and duration of storms then affect the amount of trash that is flushed into the lake.

From USGS gauging station records, CUJL counts the number of lake level rises greater than 2 ft between cleanings of various sections of the shoreline. The nonprofit found that an increase in trash does not automatically happen with every rainfall event. Instead, the lake level rises that are low in magnitude and result from low intensity and short duration rainfalls don’t flush as much trash into Jordan Lake as rainfall events with heavy and long-lasting rains. Unfortunately, more intense storms are expected to rise, just like the water levels at Jordan Lake. The latest North Carolina Climate Science Report outlines that extreme rainfall events are becoming more common for North Carolina and the rest of the world.

“It’s hard to convince people that you need to take action to protect Jordan Lake,” says DiGiano. “It’s not too different from climate change.”

Since Hurricane Matthew in 2016, the Carolinas have experienced two 500-year floods, a 1,000-year flood and some of the strongest hurricanes in decades.

According to the N.C. Climate Science Report released in March 2020 by the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies, extreme rainfall and flooding is projected to increase. The report outlines an assessment of historical climate trends and potential future climate change conditions and impacts in North Carolina. The report explains that heavy rain is becoming the “new normal.”

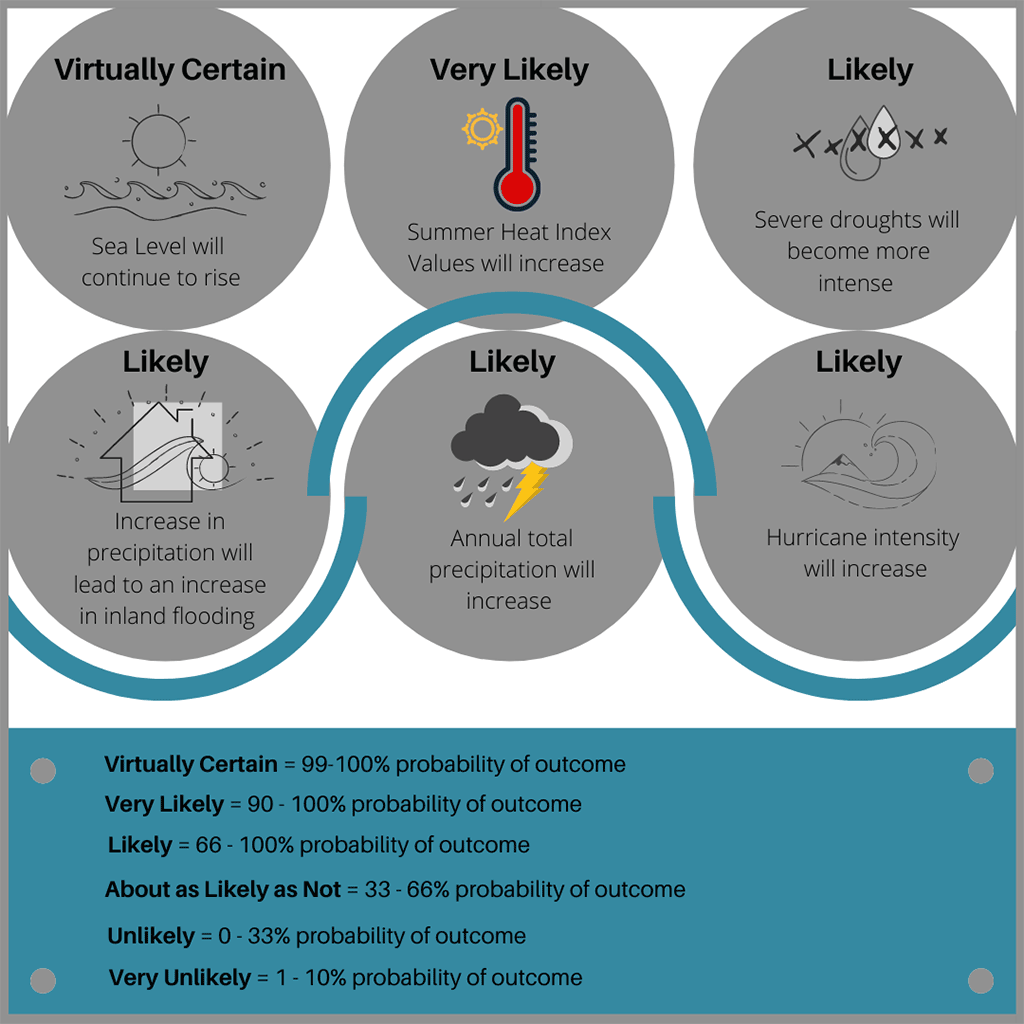

This study uses two global average temperature projections that are: RCP8.5 and RCP4.5. By the end of this century (2089 – 2099), under the higher emission scenario (RCP8.5), the global average temperature is projected to increase by about 4 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit compared to the climate we experience now. The other projection for a lower emission scenario (RCP4.5) projects an increase of about 1 – 4 degrees Fahrenheit. Either way, the earth is warming, causing glaciers to melt and oceans to warm, which adds water vapor to the atmosphere. Warming oceans create moister air, which fuels more severe and intense storms. You can view the infographic of some of the report’s projections for North Carolina below.

“We add this much carbon to the atmosphere that warms the planet and a warmer atmosphere will have more water vapor, and so then you just have more of an ability to have much heavier rainfall events when you do have this precipitation. We expect this to continue. Now the level of that depends on how much more carbon we put into the atmosphere,” explains Adam Terando, an author of the North Carolina Climate Science Report and USGS Research Ecologist with the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center.

We are already seeing more storms with heavy rainfall (3 inches or more in 24 hours). In the last four years (2015-2018), we have seen the greatest number of heavy rainfall events since 1990. These extreme rainfall events are very likely to increase. Extreme precipitation events can be deadly and destructive, even if they aren’t hurricanes and are simply large storms that create devastating flooding.

In a recent study from UNC-Chapel Hill, Professor Hans Paerl and other researchers concluded that North Carolina is seeing an increase in storms with heavy rainfall and this regime change is likely caused by a warming climate. The researchers examined 120 years of weather data, most collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). They wanted to find out if these events are random or a trend. Is North Carolina unlucky, or are we seeing a regime shift?

“We were very surprised when looking at the long-term database going back to 1898,” says Hans Paerl, Kenan Professor of Marine and Environmental Sciences at the UNC-Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences. “When you look at that data, six out the seven wettest storms datasets that we’ve had occurred in the last 20 years. That is a pretty amazing change in precipitation associated with these storm events.”

The research team calculated the probability of the flooding happening by chance at 2%.

Paerl, who is the lead author of the study published in Nature Research’s Scientific Reports, says, “One thing you can definitely say about climate change is that things are getting more extreme. The extremeness is becoming more common. That’s what’s meant by the ‘new normal’ phrase.”

For example, Hurricane Florence lingered near the North Carolina coast for 53 hours, becoming the wettest tropical cyclone on record for the Carolinas. Over four days, roughly nine trillion gallons of rain fell on North Carolina. Some areas received nearly three feet of rain. In some areas, flash and river flooding submerged entire towns.

Catastrophe risk modeling firm AIR Worldwide estimates that the industry insured losses that resulted from Hurricane Florence’s winds and storm surge ranged from $1.7 billion to $4.6 billion. The Associated Press reported that an economic research firm estimated that Hurricane Florence caused around $44 billion in damage and lost output, making it one of the top 10 costliest U.S. hurricanes on record.

Rising thunderstorms, tornadoes and extreme storms for the Piedmont Region of North Carolina

In terms of local impacts to the Piedmont region of North Carolina, the North Carolina Climate Science Report says, “based on the virtual certainty that water vapor in the atmosphere will increase as global warming occurs, it is very likely that the risk of extreme precipitation will increase everywhere in the Piedmont.” Thunderstorms and tornadoes are also expected to occur more frequently. The Climate Risk Assessment and Resilience Plan and UNC study explain that these events will increase the potential for flooding in not only coastal areas but inland areas, as well.

“These storms are going to happen more often and be more intense and we’re going to see places flooding that aren’t necessarily in typical flood zones,” says Emily Sutton, a local resident and Haw River Assembly Haw Riverkeeper. The Haw Riverkeeper is the leading watchdog against pollution in the Haw River, covering issues like emerging contaminants, Jordan Lake nutrients, and sediment pollution.

Flooding’s impacts

The impacts of flooding are severe. It was one of the main reasons Hurricane Floyd, Mathew and Florence were so deadly and catastrophic. Flooding is the leading cause of death following a hurricane. Flooding can also cause toxic discharge from large manufacturing facilities into the local watershed, damage public and private property like homes or roads and leave vulnerable populations at risk of not being able to escape flooded areas or extreme weather events.

Further inland, flooding will place a massive strain on outdated or undersized storm drain infrastructure, which can lead to more severe floods and damage. Protective habitats, fisheries and local services could be severely damaged or destroyed. Flooding can even wipe away an area’s cultural heritage. Archaeological and historic sites on floodplains within every river basin in the state are at risk.

Has Jordan Lake experienced similar rainfall patterns?

In response to Hurricane Florence in September 2018, water levels at Jordan Lake rose almost 15 feet. According to the Corps of Engineers, the lake was still six feet over its normal level a month after Hurricane Florence. The water level didn’t begin to fall until the Corps of Engineers released water over the dam, which caused an concerns amongst downstream communities. These extreme precipitation events affect more than the height of the water. Things like the current patterns, pH, dissolved oxygen, water temperature and turbidity, or clarity of the water, are also affected.

Extreme rainfall during any one storm event has already begun. For example, three of the biggest floods on the Haw River in the past 25 years have happened since 2018. This brings us back to the trash once again.

The NC Policy Collaboratory’s UNC Jordan Lake Study describes extreme rainfall events concerning Jordan Lake, saying, “Remarkable amounts of floating debris often accompany these events, with both natural and human sources.” Currently, the extent that the debris directly impacts water quality is largely undocumented.

“You have to be aware of the fact that with these extreme rainfall events, everything is going to be more mobile on land,” says Paerl. Heavier rainfall can carry more objects from land to water, and as we’ve seen an increase in this trend, one should consider the things we leave in the yard. Flooding will arise in places that hadn’t experienced flooding in the past. Flash flooding will happen more often. More trash will enter Jordan Lake.

Sutton describes the importance of the study, saying, “because there was so much modeling and different numeric levels and scenarios that were researched, we can really confidently look at the proposed solutions with an eye on outcomes because we have the data now.”

This report creates a solid scientific foundation for decision-makers to fix our water quality problems. In the meantime, pick up some trash. Jordan Lake desperately needs it.

Photos courtesy of Clean Jordan Lake and the UNC Jordan Lake Study Report.

Mary Claire McCarthy is a second-year graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Upon completion of her thesis research this fall, she will finish the Dual-Degree Environmental Science Communication Program. Her research focuses on how communicators can use advocacy communication to bring awareness of the effects of climate change on national forests such as the Pisgah National Forest and remarkable ecological regions like the Blue Ridge Appalachia to drive behavior change and participation in environmental grassroots effort amongst Generation Z. If you would like to reach her to discuss this research, her email is mclaire7@live.unc.edu.