How state government agencies, local governments, nonprofits and landowners are harnessing the power of land conservation to restore and protect drinking water for hundreds of thousands of Triangle residents.

By Mary Claire McCarthy

Jordan Lake—Central water supply source, recreation haven, flood control measure and Bald Eagle sanctuary

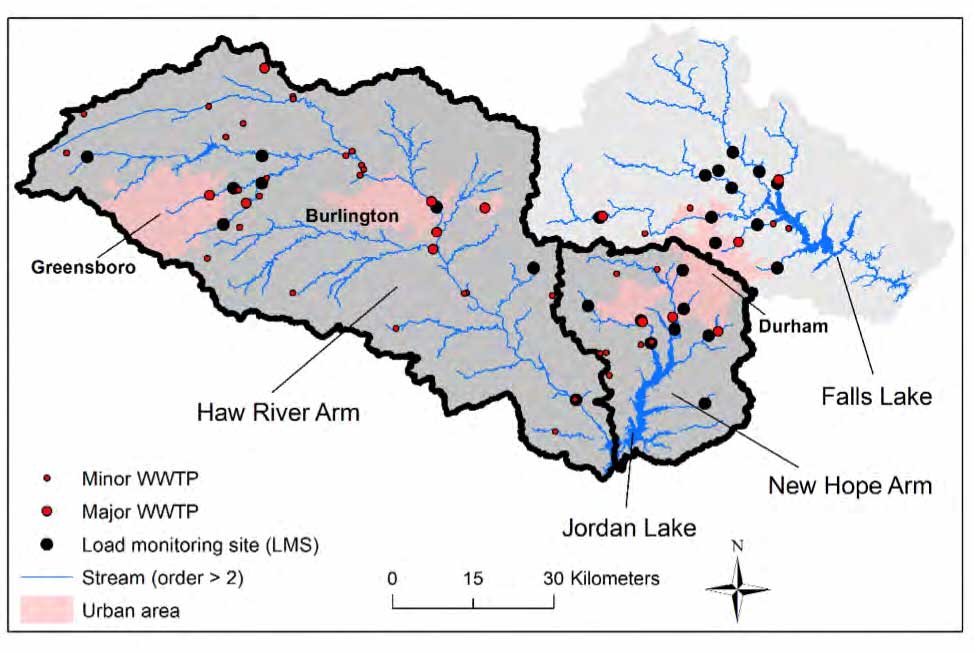

We typically don’t consider where our tap water originates. The answer is as interconnected as the system of waterways that carry water to our faucet. Our drinking water resides in a watershed or a land area that channels rainfall and snowmelt to creeks, streams and rivers into larger bodies of water like reservoirs or the ocean. For many Triangle residents, our drinking water springs from the Jordan Lake watershed, which is a 1,687 square mile area situated in the middle of North Carolina, stretching from Rockingham County to Wake County.

Jordan Lake serves a mixture of purposes. It provides clean drinking water for nearly 700,000 Triangle residents and recreation for a million visitors each year. The lake and surrounding forests also provide critical habitat for plant and animal species and flood control for downstream regions.

The watershed encompasses some of the largest urban areas in North Carolina, namely the Triangle and the Triad. Both have seen significant growth and development over the last 40 years, which can degrade the quality of our drinking water as land is gobbled up to meet the demands of a rapidly growing population. Only 8% of the Jordan Lake watershed (about 88,000 acres) is protected from development. Of the remaining unprotected land, 70% are undeveloped lands that include forests, fields, farms and wetlands. From 2011 to 2016, the National Land Cover Database estimated that developed land increased by almost 13% in the watershed, demonstrating the risk urbanization poses to ensuring water quality for generations to come.

We’ve all seen algal blooms. They are the large mats of green slime that crowd around the edges of lakes. Sometimes they are even large enough to reach deep into the center of the lake. You can find them at Jordan Lake. The algal blooms are not particularly dramatic at Jordan Lake, since much of it is in the water column itself, rather than in large blooms on the surface. This is what gives Jordan Lake the characteristic green color when seen from a boat or while in the water, compared to the water appearing blue when driving over it from say, a bridge.

Since its creation water quality issues have plagued Jordan Lake, with the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission declaring the waters as nutrient-sensitive the same year it was created. Since that time, the nutrient levels present in Jordan Lake have been above EPA standards. Under the Clean Water Act, North Carolina is required to clean up these pollutants. These nutrients, namely nitrogen and phosphorous, over-enrich water and sediment in the reservoir, leading to nuisance algae blooms that quickly crowd out other crucial plants and aquatic life.

These algae blooms are a prime indicator of eutrophication, and a large concern for water quality management. They occur largely throughout the year in the upper reaches of the lake where the nutrients first enter. Agriculture and fertilizer application, pollution from wastewater discharges and stormwater runoff from new and existing development bring these nutrients and other pollutants into the lake.

Algal blooms can affect the taste and odor of drinking water supplies, increase water treatment costs and hurt industries that depend on clean water. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, harmful algal blooms can also include dangerous toxins that can sicken or kill people and animals. Even nontoxic blooms hurt the environment and local economies.

Conserving the upstream land, streams and creeks are some of the best ways to protect the water we drink. Water from creeks and streams flow downhill into rivers that eventually wind up in a larger body of water. As the water flows downward, it picks up pollutants, which can harm the ecology of the watershed, and ultimately, the drinking water sources we depend on. Forests, wetlands and open fields slow down rain and runoff by filtering the water through the soil, trapping pollutants and sediment. Pollution is then kept in the soil instead of flowing into the lakes or reservoirs that are used as drinking water supplies.

Protecting the land in a drinking water supply watershed is one of the most effective and inexpensive strategies for restoring and protecting our drinking water. The diverse set of stakeholders in the Jordan Lake watershed understand this, which is why it is a key component of the current watershed management framework.

Jordan Lake stakeholders work together

Since its creation in 2017, Jordan Lake One Water Initiative (JLOW) has worked to develop and implement an integrated watershed management strategy, i.e. a “One Water” framework, for the Jordan Lake watershed. This strategy works alongside other management tools in an effort to restore and protect the water quality of Jordan Lake through land conservation. Watershed protection is one of the central elements of the initiative’s mission. The initiative facilitates collaboration among a diverse set of stakeholders in order to develop policy, operational and financial recommendations to address the regulatory concerns of the Clean Water Act. JLOW stakeholders have met quarterly to learn about One Water, and to share diverse perspectives, local community-based challenges and objectives and thoughts on the deployment of the actual management strategy.

One of the unique characteristics of JLOW is a focus on achieving multiple goals—economic, environmental and social. Coupled with this, JLOW utilizes watershed-scale planning that places a strong emphasis on integrating individual community needs into the larger collective vision of the entire watershed. This focus increases opportunities for upstream, downstream, urban and rural entities to work together to implement multi-benefit projects.

“Finding these tools that meet several different goals makes this collective group of stakeholders more willing to make changes,” says the Haw River Assembly’s Haw Riverkeeper Emily Sutton. The Haw Riverkeeper is the river’s main watchdog, a non-regulatory position that carries the responsibility of protecting the watershed. Sutton oversees water quality issues in the Haw River, including emerging contaminants, Jordan Lake nutrients and sediment pollution. The Haw River Assembly is also one of the stakeholders involved in the JLOW Initiative.

Last year’s historic flooding in Greensboro provides an example of how water quality programs and actions can help address problems in upstream communities and the nutrient issues in Jordan Lake. The city of Greensboro experienced historic flooding last year that left city officials and residents unprepared as they were undulated with flash flooding. Sutton explains that it is possible to manage the City of Greensboro’s flooding through different stormwater management systems (e.g. green stormwater infrastructure and land conservation) that also impact the nutrient problem in Jordan Lake.

“I mean upstream dischargers, whether its waste water treatment plants or industrial plants or cities with nonpoint source pollution, know that something has to give. They’re ready and willing to change practices and have more strict regulations to protect water quality in Jordan Lake,” said Sutton.

JLOW Initiative partners have brought together an average of 60 or more representatives of organizations and stakeholders, many of whom are collaborating across jurisdictions for the first time. By relying heavily on partnership and inclusion, JLOW has created a forum for ongoing dialogue among a diverse set of stakeholders, such as local governments and agencies.

“In the past, these stakeholders tended to come together for different things like water allocation and rules development but this is the first time the entire group has come together in a more voluntary and proactive effort to come up with different ideas and strategies, said Leigh Ann Hammerbacher, director of Land Protection & Stewardship (East) at the Triangle Land Conservancy.

Harnessing land conservation to safeguard clean water

The Triangle Land Conservatory worked with One Water partners to create a Jordan Lake Watershed Conservation Strategy that identifies key parcels of land for conservation. One Water partners and the Triangle Land Conservatory have identified a goal of protecting 35,000 acres over the next 35 years, which corresponds to about 5% of the eligible acreage within the watershed. This conservation strategy was modeled after the successful Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative (UNCWI), which has received national recognition for its expansive efforts to protect drinking water and the crucial watersheds supplying it.

The UNCWI is a 14-year old conservation program created to protect and provide clean water for the Triangle region. The Upper Neuse watershed includes 770 square miles, six counties and nine water supply reservoirs, including Falls Lake, the primary water supply for Raleigh. Falls Lake was also similarly impaired due to high levels of turbidity and chlorophyll-a.

The Upper Neuse watershed also shares similar demographics and land uses with the Jordan Lake watershed, suggesting that a similar conservation effort can succeed in the Jordan Lake watershed. Even in the midst of a global pandemic, local cities are committed to protecting clean water. In the past month, the City of Cary allocated $765,000 in the city budget to support watershed protection activities! This was made possible by the demonstratable success of the UNCWI Initiative.

The UNCWI brings together landowners, conservation organizations and local and state government programs to protect Falls Lake, amongst other water resources. Initiative partners work with landowners, local governments and the public to review land conservation options and acquire key parcels of land through voluntary purchase or donation of land or conservation agreements. The Jordan Lake Watershed Conservation Strategy modeled its approach in a similar fashion based upon the nationally recognized UNCWI.

UNCWI partners have completed over 90 projects protecting 8,048 acres and land along 89 miles of streams. Once the 10 projects currently underway are completed, the initiative will have conserved 10,000 acres and more than 100 miles of streams. Based on research by the North Carolina Forest Service, the UNCWI estimates that conservation efforts have resulted in a pollution avoidance of almost 5,700 pounds of nitrogen and 1,000 pounds of phosphorus per year.

A key component of the strategy relies on securing funding from a wide range of sources and the program has done just that. For example, for every $1 invested by the City of Raleigh Public Utility Department, UNCWI and the nonprofit land trusts that serve as partners in it have leveraged $7. The City of Raleigh’s investment comes from Raleigh water users paying a $0.15 fee per 1,000 gallons of water—less than the cost of a water bottle. These small monthly allocations are based on water use and average only $0.66 a month per household, so for less than $8 a year, Raleigh water ratepayers are able to contribute to a program that, in return, secures a projected $24 million a year from other resources to put towards conservation projects.

“Land protection is the low hanging fruit,” says Hammerbacher.

For the past decade and a half, state policy-makers, regulatory agencies, local governments and a range of other stakeholders have worked to restore water quality within Jordan Lake, with little success. Land conservation is proving to be a complementary strategy that all stakeholders can agree upon, and one that demonstrates tangible results as well.

For example, undeveloped land export ten times less nitrogen and phosphorous compared to agricultural and urban lands, according to the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory’s latest Nutrient Management Report. Restoring and retaining land buffers along streams is one of the most cost effective strategies for reducing nitrogen loads in a watershed. Studies demonstrate that nitrogen, phosphorus, sediments, pesticides and other pollutants are reduced by 30 to 98% in water that has passed through forested land with these buffers. You can find these studies and facts in the literature review of the Jordan Lake Conservation Strategy.

Protecting natural watersheds also saves communities money. It lowers costs associated with expensive treatment plants or upgrades needed to purify water in degraded watersheds—saving money for municipalities and utilities. For example, a 2011 study by the Industrial Economics, Inc. found that a loss of 3,132 acres of wetlands over 15 years equated to $840,000 in annualized municipal water treatment costs, or $281 per acre per year.

Land conservation provides other community benefits, as well. Conservation creates new parks and greenways and protects a host of ecological services, such as flood protection, air purification and pollination.

For less than one bottle of water a month, users of Jordan Lake have the opportunity to contribute to a program that permanently protects thousands of acres of land, increases recreation possibilities, protects and enhances local farms and possibly most importantly, safeguards clean drinking water for future generations.

“The fact that we’re able to learn from neighboring water strategies and implement a strategy that will have perpetual, permanent and long-term impacts,” is one of the most promising aspects of the Jordan Lake Conservation Strategy, says Hammerbacher.

Mary Claire McCarthy is a second-year graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Upon completion of her thesis research this fall, she will finish the Dual-Degree Environmental Science Communication Program. Her research focuses on how communicators can use advocacy communication to bring awareness of the effects of climate change on national forests such as the Pisgah National Forest and remarkable ecological regions like the Blue Ridge Appalachia in order to drive behavior change and participation in environmental grassroots effort amongst Generation Z. If you would like to reach her to discuss this research, her email is mclaire7@live.unc.edu.