By Caroline Patterson

Almost every North Carolinian has seen the blue outlines of the Appalachian Mountains, a feature which has made western North Carolina so memorable. The Blue Ridge Parkway, pride and joy of the state, is a major factor in North Carolina’s appeal. While being featured in blockbuster films like The Hunger Games and The Fugitive, the mountains of western North Carolina have become known as one of the most wild and natural places on the East Coast. With growing concerns of climate events in the coming years, this is one ecosystem that North Carolinians are looking to protect.

Wildfires have been a subject in the news in the past few years, and 2016 was a year for unprecedented wildfires on the east coast of the United States. Starting in 2019, UNC has implemented the preliminary stages of a new NC Policy Collaboratory project to discover the connections and relationships between wildfires and landslides in the western North Carolina mountains. California has conducted extensive research to describe the relationship between wildfires and landslides, yet North Carolina has little evidence of this relationship and the impacts on our communities.

Project leader Susan Cohen is the associate director of the Institute for the Environment at UNC-Chapel Hill and has had extensive experience in the field of biology. After watching the events of the California wildfires in recent years, Cohen recognized the need for a project in the western mountains of North Carolina to research the relationship between wildfires and landslides with the state’s specific context in mind. With the help of the Collaboratory, Cohen created a team to conduct research in the regions where landslides would most likely occur.

Along with Cohen, the contributors on the project are Jennifer Bauer and Stephen Fuemmeler from Appalachian Landslide Consultants, Robert Eaton from the US Forest Service Southern Research Station, Julia Maron from the UNC Chapel Hill Institute for the Environment, and Corey Scheip, Jesse Hill, and Rick Wooten from the North Carolina Geological Survey.

What is the Project About?

Cohen described the project as an early investigation into the connection between landslides, specifically debris flows, and wildfires in western North Carolina. The eastern U.S. has not had enough research and the wildfires in 2016 were a wake-up call. “If there is a connection, we need to start understanding predictions and management options to try to mitigate the impact to life, property, and economic factors like tourism,” Cohen suggests.

The goal of the project was to determine if there is a correlation between debris flows and wildfires. Where the project stands right now, researchers are asking whether there is enough evidence to suggest they should go deeper into the study to see if there is a causal relationship. If there is not a relationship, stakeholders will know that wildfires will not significantly impact management practices and prediction models. “But if there is a connection, it would be really important to understand how probability [of a debris flow] changes post-wildfire; so early warning systems or construction projects that may be impacted could be better planned for,” says Cohen.

Cohen mentions that the whole nature of this relationship seems different between the east coast and the west coast. “We learned enough to know that there are some interesting things happening. Some of the difference between the east and the west are the severity of fires, vegetation, and recovery time.”

The North Carolina Geological Survey, or NCGS, falls under the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources Division of Energy, Mineral, and Land Resources. Their landslide hazards team currently maps landslide hazards in western North Carolina. Richard M. Wooten, a Senior Geologist for NCGS, focuses on studying these debris flows from burn areas.

A debris flow is more commonly referred to as a mudslide, which is triggered by heavy rainfall events. Wooten says that the debris flows can move down a hill up to 30 miles per hour and can be very destructive.

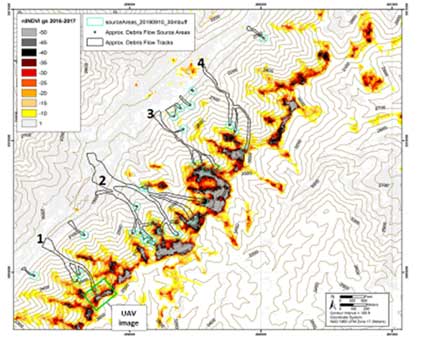

“Our role in the study is looking at the geological connections between debris flows and when they happen and burned areas,” Wooten said. One way to do this is by observing vegetation levels. “Vegetation is an important factor for debris flow susceptibility,” as it is known to help stabilize mountain slopes. Wooten and the team want to get a better understanding of vegetation change from wildfires and their vulnerability to debris flows. Along with vegetation, a few other factors are being observed, such as evapotranspiration and soil moisture level.

Why is This Important?

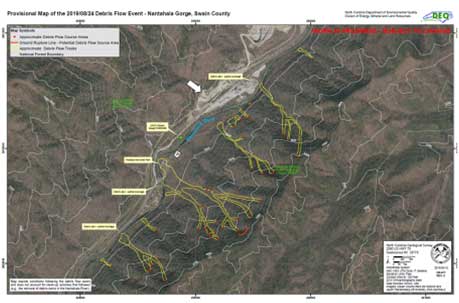

Why is this data so important to begin to understand? Wooten explains that the debris flows and landslides in 2016 caused a lot of damage. All the major debris flows started either in or below the major burn areas in 2016. Near the Nantahala river gorge, these events have been estimated to cost over one million dollars in damage, which impacted road reconstruction efforts and white-water recreation. “It’s expensive number one, a big economic loss and we were fortunate no one was injured in those debris flows. People can get trapped,” Wooten said.

The NCGS has found that there is a strong physical correlation between burn areas and debris flows, but they have not yet sorted out the mechanism that made those areas more susceptible. Future reports will determine what these mechanisms are in the mountains of western North Carolina.

Public safety is one of the main reasons the NCGS is involved. One of the biggest threats to public safety from landslides in North Carolina are debris flows. “You always hear about the big rock slides on I-40 that stop traffic where the roads are closed for months sometimes, but not of the resulting destruction of homes and human lives from debris flows,” Wooten said.

Landslides in NC

“Understanding landslides allows us to connect geology in order to help communities like my own,” said Jennifer Bauer, co-owner, and founder of the Appalachian Landslide Consultants.

Bauer recognized that landslides happen almost every year in western North Carolina. Bauer and Stephen Fuemmeler created Appalachian Landslide Consultants in order to provide landslide mapping and property evaluation services for the communities of Appalachia.

Appalachian Landslides Consultants are working with the project team to help identify appropriate sites to collect data and with the data collection process. Bauer believes in the need for landslide research because of its benefits to local communities.

High record rainfall years and changes in climate might make this research even more important. “Yet we also see drought years where fires are happening, so we know there is a correlation in other parts of the country in California and Colorado,” Bauer said.

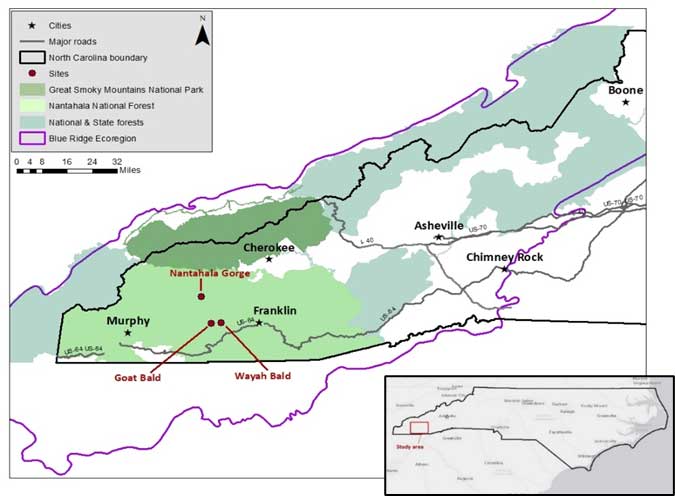

The team targeted areas that had been burned and not burned. They then looked at available landslide models to identify areas that have a higher likelihood of initiation debris flow style landslides. Debris flows occur when the soil gets too saturated and it lets loose a mixture of soil, rocks, and trees which can flow for many miles. By looking at the models where natural debris flows might start, the team selected areas to study that represented burn and no-burn conditions in landslide prone areas in western NC. Study sites were in Macon County, Wayah Bald and Goat Bald, and the Nantahala Gorge in Swaine County. Both counties are in the Blue Ridge region of the North Carolina mountains.

“We know that landslide mapping is really important for people to understand where they are living and the hazards around them, and having an understanding of how this relates to wildfires builds on the understanding of where landslides are happening in general,” Bauer said.

Looking to the Future…

Understanding economic consequences of debris flows will be a driving factor in the continuation of studying wildfires and landslides in North Carolina. Wooten said that an increase in extreme weather patterns, droughts, and wildfires or above normal rainfall, is setting up for more debris flows and community impact in the coming years.

Bauer said that it is important to understand that it is the beginning of the study and that we need to study additional data sets over many years in order to make definite conclusions. The goal is to better understand what is happening to better forecast these events before they happen. With the unpredictability and increase in intensity of rainfall events expected in the coming years, these events will become even harder to predict, making it important to continue research of landslides relationship to wildfires.

Caroline Patterson is a senior Environmental Studies and Public Policy major at UNC-Chapel Hill and an intern with the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory.