By Claire Bradley

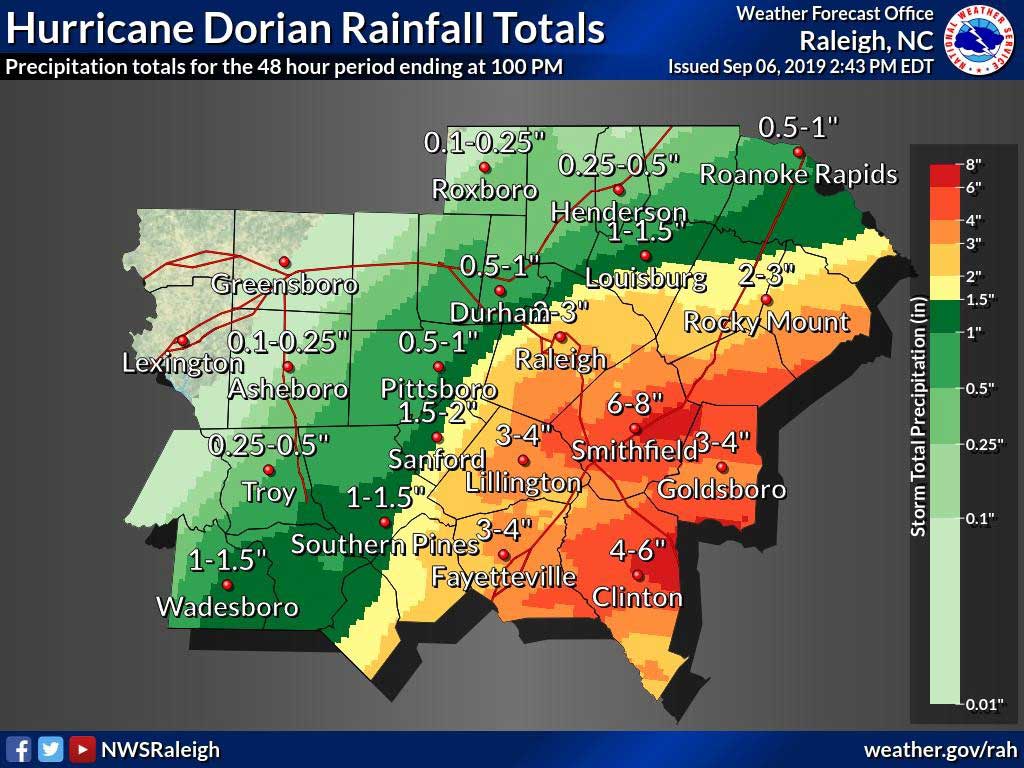

In recent years North Carolina has seen powerful hurricanes cause significant damage, including loss of life and devastating economic impacts across the state. With trends pointing to an increased number of powerful storms, coastal communities and ecosystems will face more damage and longer-lasting flooding.

To combat this, scientists are studying resiliency with policy in mind; how to enact policies that take a preventative preparedness approach and will be fast acting so when floods occur from these big storms, communities have the resources to bounce back.

University Scientists Work to Strengthen Resiliency Efforts

In 2019 the North Carolina General Assembly passed a comprehensive disaster recovery policy, Senate Bill 429, “Disaster Recovery Act.” Included among its provisions was $2 million in funding for the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory to study flooding and resilience in eastern North Carolina in hopes of improving the future efforts of protecting the coast and its people.

The project consists of of sixteen researchers across many different subprojects managed by professor Mike Piehler, director of the UNC Institute for Environment. These individual projects include research on:

- floodplain buyout policies,

- energy infrastructure, wastewater/water infrastructure,

- natural systems,

- public health; and

- financial risk to communities.

This unique collaboration has brought together highly experienced researchers from UNC-Chapel Hill, NCSU, NC A&T, and Duke. The full project team will submit its recommendations to the legislature in December of 2020.

A Closer Examination of Public Health Impacts

Of particular interest and the focus of this article, is the public health component of the project spearheaded by Jill Stewart, professor at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and professor Rachel Noble at the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences.

Generally, they are examining the risks of microbial contaminants that are associated with flooding in eastern North Carolina. They established that there are a fair number of “unknowns” regarding the distribution and duration of impacts of flooding so to address that the first part of their project was to establish a baseline of water quality in the North Carolina aquatic systems. This allows them to compare those conditions and levels of bacteria and virus counts to the contaminants measured during and after storm and flood times.

In an interview with Dr. Stewart she emphasized the importance of being able to understand baseline conditions. She explained how without those measurements, it is unknown whether the post-flooding measurements are elevated normally or elevated as a result of the flood.

“Usually there is a lag between a major event and when people start doing any sort of research, but in this case, we were uniquely positioned to do good work since we were already doing water and land use impact work on surface water quality.”

Dr. Stewart has historically done similar research after Hurricanes Matthew, Florence and Dorian. She explained that it was that prior work that enabled her to react so quickly after Dorian.

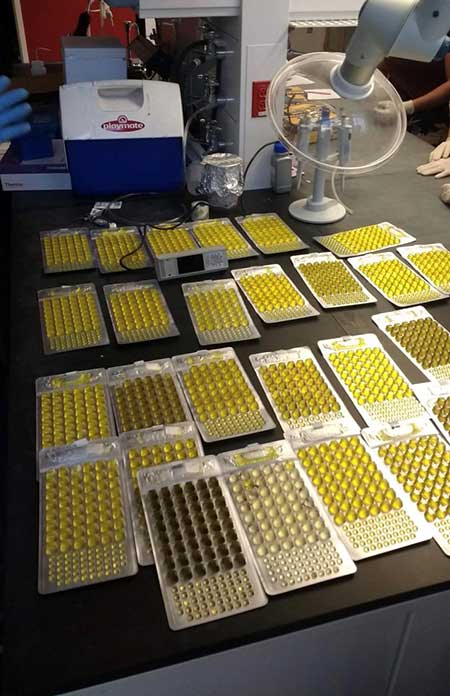

Her team was testing just a week after the storm hit. Though reaction is typically much slower, sometimes physically impossible due to road blockages, she explained, having already been out in the field and familiar with the study sites allowed her team to expedite the process and take samples that were more representative of storm-like conditions.

From this data, measurements of pathogen, fecal source, fecal indicator bacteria, fecal indicator virus and antibiotic resistance analyses were taken. This project continues to expand this data set as well as contribute to the larger resiliency portfolio project going on.

Assessing the Impact of Storms on Drinking Water Wells

Over 3.3 million residents in North Carolina—just about one-third of the population—rely on private wells as their primary drinking water source.

One interesting component of the public health work is research on private drinking water well quality. Drs. Stewart and Noble are contributing to a project the National Science Foundation is conducting by performing pathogen analyses on samples the project collects. One component of this work is a big community outreach push that is planned for this summer in collaboration with many groups in North Carolina.

The goal is to inform and educate the inhabitants of the area about the quality of the water and the resources to address water quality concerns. The owners of any specific private wells that are flagged as concerning will be notified of the status of their well with recommendations of how to address it.

With any research being conducted, the goal is to translate the findings to actionable items to improve the conditions studied. This has historically proven to be easier said than done but with this specific study, Dr. Stewart described how she was “really excited about how this project is set up” because its design was specifically to be able to translate to recommendations and then collaborate with the state legislature to ensure that the best solutions are implemented. This way, researchers know that they are working towards a set of recommendations that they can ascertain will be used to better the lives of coastal North Carolinians.

A main component of what will inform the recommendations are the models being created. Drs. Stewart and Noble are hoping to use the data collected from the field sampling to create models that will predict when water quality will be above safety standards and when it will not be based on timing. Dr. Stewart is especially pleased with the spatial representations as they are able to model distance metrics.

This type of data visualization enables people to look at where the most impacted wells are located and where the hazard regions are. To date, the main datasets being mapped are the surface water sets as those are the best figures because the research team was able to get baseline measurements. They hope to expand into the private well data as the project continues.

As with many other projects, this one has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated stay at home orders. Many of the samples were still being processed when the interruption occurred. Luckily for the research team, they had already conducted the time-sensitive analyses so much of what will get delayed is the molecular analysis that can be done at any time. After this delay they plan to continue analysis and spatial modeling before the December deadline for the whole project to be submitted.

Claire Bradley is a junior Environmental Studies major at UNC-Chapel Hill and an environmental policy intern with the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory.