By Taylor Fitzgerald

Origins of the Collaboratory’s “Operation Deep Freeze” Project

When the COVID-19 vaccine became available for administration in December of 2020, organizations such as the NC Policy Collaboratory rushed to devise a plan to get vaccines into the arms of community members. The vaccine was a much-needed light at the end of the tunnel, and is still a key part of gaining control of the COVID-19 pandemic and slowing the spread of disease to save lives. With the news of the COVID-19 vaccine release, Jeff Warren, the Collaboratory’s executive director, knew the Collaboratory could play a major role in distributing vaccines across the state.

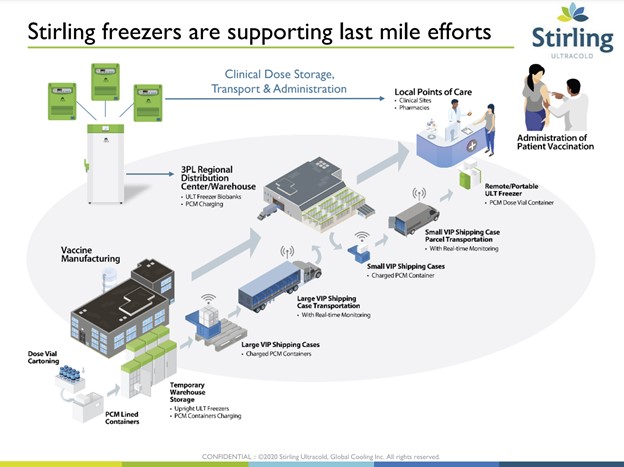

One challenging aspect of effectively distributing COVID-19 vaccines is making sure they are kept at the correct temperature all the way up until the moment they are administered. The process vaccines go through to their destination includes everything from vaccine production, storage and transportation, all the way up until a patient receives a vaccine, a process known as the “cold chain”. So, what is the solution to the vaccine’s need to be kept at extremely low temperatures? Stirling Ultracold has the answer.

Stirling Ultracold’s Adjustable and Portable Freezers Act as a Solution to the Collaboratory’s Vaccine Distribution Plan

Mark Brown, a Sales Director for Stirling Ultracold, explains the background of Stirling Ultracold’s adjustable and portable freezers and how these freezers are addressing vaccine disparities between urban and rural communities. Brown states that although these freezers were made originally for purposes such as storing samples in biorepositories, for cell and gene therapy and life sciences research, Stirling foresaw these freezers being utilized for widespread COVID-19 vaccine distribution in North Carolina. In fact, “Stirling as an organization has been involved all the way through the ‘cold chain’,” Brown says, explaining that the cold chain is “everything from the beginning manufacturing process of the raw materials for a [vaccine] all the way until [a vaccine] gets into a patient’s arm.”

As a part of the final stage of the “cold chain” Stirling’s freezers help address a challenge unique to COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccines that are mRNA based such as COVID-19 vaccines require extremely cold temperatures to stay effective as mRNA are uniquely vulnerable to degradation. Additionally, original COVID-19 vaccine storage requirements varied between the different types of vaccines offered. For example, Pfizer vaccines required a storage temperature of -70°C whereas Moderna’s requirement was between -50°C and -15°C. Stirling Ultracold’s portable freezers offer storing temperatures that range from -20°C to -80°C. These freezers offer the perfect solution to the COVID-19 vaccines’ need for extreme cold and varied temperature storage needs and help to reduce vaccine waste, leading to more vaccines being successfully administered.

Reaching Underserved Communities

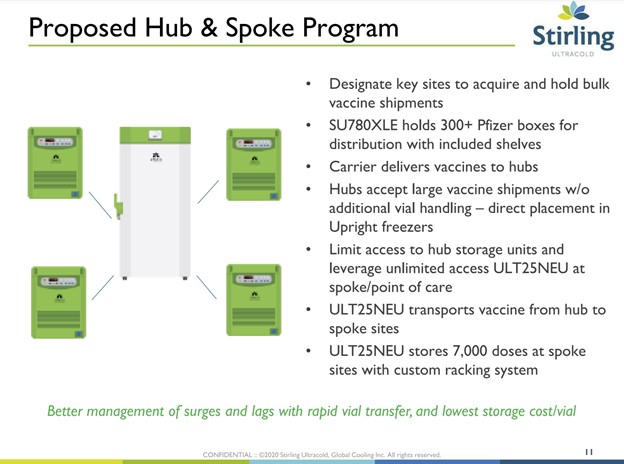

A large force behind the Collaboratory’s “Operation Deep Freeze” initiative is creating the ability to provide underserved communities with access to COVID-19 vaccines that they may otherwise lack. Mark Brown explains that “most of the [vaccine distribution] efforts were around getting to the much larger urban populations” with many vaccine hubs being placed in these areas. Brown also explains that the Collaboratory took a much broader approach than many, taking steps to reach more effectively its “patient population and serving their needs” through the use of portable COVID-19 vaccine freezers.

Dr. Deepak Kumar of North Carolina Central University speaks on the benefits of distributing COVID-19 vaccine freezers to underserved communities, stating that lack of storage was a large issue facing low-resource communities: “There was a lot of talk about ‘how are we going to manage the storage’” within these communities along with “how these public health departments who never had the need for having this ultracold storage are going to come up with that.”

In addition to a lack of storage available within these communities, general medical infrastructure tends to be of lower quality compared to high-resource areas, creating “a logistics inequity” when it comes to vaccine distribution. Dr. Kumar states that, through the COVID-19 grant from the Collaboratory, his team was able to provide a vaccine freezer to the Halifax County Public Health Department, making it possible for this area to receive its first shipment of the COVID-19 vaccine that would not have been possible otherwise due to lack of assured storage available. Additionally, freezers were distributed to the Durham Public Health Department and the Lumbee Tribe in Robeson County, increasing vaccine accessibility in these areas.

Looking Ahead

Dr. Kumar explains that increased access to storage freezers will continue as the COVID-19 vaccine has become available to children. Prior to this authorization, his team placed a freezer in Lincoln Community Health Center to expand vaccine accessibility in preparation for increased demand as wider demographics are approved for vaccination. He also explains that with waning immunity that requires booster shots for many at risk groups, meaning that the vaccine storage issue seen in the initial stages of vaccine distribution will continue to be an issue further down the road. In order to address this issue, he states that, “we need to make sure that the providers who are giving vaccines in different communities, especially hard to reach and low-resource areas, have the ability to store the vaccine.”

Mark Brown also speaks on the future of “Operation Deep Freeze” stating that the Collaboratory’s approach is unique as those who implemented freezer distribution are “going back and looking at what did [they] do right and what ultimately was the outcome.” One way this is being done is through the installation of “external monitoring systems” on freezers throughout various vaccine storage sites. This allows for evaluation of how the vaccine is being used, vaccine use efficacy and storage issues that give insight into how the project should look in the future to be more impactful and effective.

Brown also explains that increased demand for vaccines has led to global supply chain issues, making this “a challenge that is going to be with us for a long time.” He also states “the beauty of what UNC has done though is there is infrastructure in place that can be utilized for ten to fifteen years” that lends itself to various methods of vaccine distribution along with other products and therapies that require long term storage.

Such infrastructure created by the Collaboratory’s “Operation Deep Freeze” has opened many doors for the UNC system, creating a future full of potential initiatives COVID-19 vaccine related initiatives and beyond.

Learn more about the Collaboratory’s COVID-19 projects.

Taylor Fitzgerald is a second-year graduate student completing a dual degree in Environment and Science Communication with a concentration in Strategic Communication.